Imigração e o Mercado de Arte Africana

*texto escrito por Alice Buratto

A partir dos anos 2000, o mercado de arte africana cresceu cada dia mais através de ações organizadas pela Bonhams e pela Sotheby’s em Londres. Atualmente se tem grandes colecionadores de arte contemporânea africana ao redor do mundo, principalmente em Londres, Paris, Veneza e Nova York.

Em 2008 foi organizada a primeira feira de arte no continente africano, ocorrendo em Johannesburg. Desde então foi criada em 2012 a Cape Town art Fair na Cidade do Cabo e a ART X LAGOS na em Lagos, constituindo-se assim Africa do Sul e Nigeria como os dois grandes polos de arte contemporânea da Africa.

Apesar, da arte contemporânea ter reconhecimento em outros países africanos, muitos artistas que são naturais desses dois polos, tem a necessidade de imigrarem para expandirem o reconhecimento de sua obra além das fronteiras de seus respectivos países.

Paulo Chavonga, artista angolano, representado pela Baka Gallery aqui no Brasil, desde cedo conquistou o prestigio no mercado de arte de Angola, estando presente diversas coleções particulares em seu país. Para expandir alem das fronteiras angolanas e luso-africanas, o artista sentiu necessidade de sair de seu país, e assim como muitos de seus conterrâneos migrou para o Brasil. Residindo desde 2016 em São Paulo, vem conquistando cada vez mais a cena artística paulistana, tendo ja participado de diversas exposições no SESC e da VII e VIII Bienal CPLP (Cuktura Lusófonas) e da Bienal Expofacic de 2019 em Portugal.

Contudo, muitos artistas migram para os próprios polos de arte dentro do continente africano, como é o caso da artista Lizette Chirrime, quem também faz parte da Baka Gallery aqui no Brasil. Lizette é uma artista moçambicana que já participou de diversas exposições na Africa e na Europa.

As trajetórias imigratórias dos artistas do continente africano muito se desenham por fronteiras socio-lingüísticas. Os artistas angolanos tem grande imersão no mercado de arte português, assim como os moçambicanos e os de São Tomé e Príncipe. Já os artistas congoleses tem mais fácil imersão na Bélgica e na França, e os sul-africanos na Inglaterra.

Tantos as trajetórias imigratórias dos artistas quanto a expansão de suas respectivas obras transcendem antigas barreiras coloniais. Assim como a colonização europeia influenciou diretamente a cultura e a estrutura socioeconômica do continente africano, a Diáspora Africana e também esses novos processos imigratórios colaboram para a construção identitária dessas localidades geográficas em que se constituem essa rede reticular migratória; criando-se assim estruturas que conectam-se social e culturalmente, seja por meio da história e de um passado comum, ou de manifestações artísticas, cientificas e/ou religiosas.

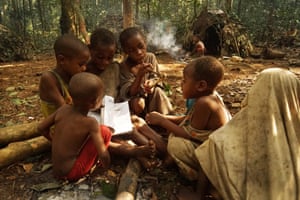

Aqui no Brasil, a Baka Gallery, constituído pela parceria da Marchand de arte Rosa Barbosa e a Antropóloga Alice Buratto, tem como objetivo principal explorar o constructo da identidade da cultura brasileira que se dá pela integração de manifestações culturais tanto coloniais, indigenas e africanas que se hibridizaram. Sendo assim, nesse projeto Rosa Barbosa e Alice Buratto apresentam obras de acervo de artistas brasileiros e africanos que exploram aspectos da identidade Afro-América. Além da arte contemporânea, o Baka Studio tem desenvolvido ao longo dos anos um acervo em arte tradicional africana, composto por artefatos históricos e sociais de diversas etnias, sobretudo da África do Sul e Camarões. Sem um modelo de representação exclusiva, Rosa Barbosa e o Baka Studio apresentam-se como mais uma plataforma de divulgação de artistas com identidades diversas.

Nascido em Benguela, Angola, residente em São Paulo há apenas 12 meses, vive a experiência de um jovem estrangeiro longe de sua família, em terras estranhas; experiência constituída a partir de um corpo-território, que é caracterizado por uma identidade imigrante-refugiado de partes múltiplas do continente africano. Todo dia é um aprendizado, em São Paulo, quem sou? Talvez uma gota num mar de artistas, trabalhadores e desempregados. Sou mais um ser humano a procura de realizar sonhos em meio à multidão de brasileiros, pintor de rua, nas grandes avenidas e nas estreitas vielas dos bairros periféricos. Sou NÔMADE.

Nascido em Benguela, Angola, residente em São Paulo há apenas 12 meses, vive a experiência de um jovem estrangeiro longe de sua família, em terras estranhas; experiência constituída a partir de um corpo-território, que é caracterizado por uma identidade imigrante-refugiado de partes múltiplas do continente africano. Todo dia é um aprendizado, em São Paulo, quem sou? Talvez uma gota num mar de artistas, trabalhadores e desempregados. Sou mais um ser humano a procura de realizar sonhos em meio à multidão de brasileiros, pintor de rua, nas grandes avenidas e nas estreitas vielas dos bairros periféricos. Sou NÔMADE.