Projetos do Baka Studio

Africa do sul:

- Artesanato social: O Baka Studio trabalha em pareceria com diversas associações de mulheres em diferentes países africanos, estabelecendo suas atividades principalmente na África do Sul e Camarões. A comercialização desses produtos representa a única forma de renda para essas mulheres e suas famílias. Na África do Sul, o Baka trabalha com uma associação de mulheres Xhosas que residem na Township de Gugoleto. Essas mulheres usam em sua produção resíduos da industria alimentícia, aproveitando, como por exemplo, ossos, chifres e peles de animais que seriam descartados no lixo.

- Design sustentável – Reaproveitamento de resíduos: em nosso ateliê na cidade do cabo, fazemos o trabalho de reaproveitamento de resíduos da industriai alimenticia local, usando assim em nossa produção peles e couros consumidos para alimentação da população local.

Brasil:

- Imigrantes Africanos no Brasil: no Brasil o Baka Studio desenvolve diferentes projetos junto com imigrantes africanos que residem na cidade São Paulo. De início, o Baka procura entender a necessidade de cada pessoa que vem em nossa instituição e se possível, ajudá-las com suas respectivas demandas. Junto a isso, os designers do Baka Studio criam alguns produtos com a colaboração de alguns imigrantes, tanto com a intenção de utilizar matérias-primas comercializadas pelos mesmos, como também oferecer trabalhos a estes imigrantes na manufatura desses produtos.

- Artesanato social: Entende-se como socialmente correto um empreendimento que contribua para a construção de uma sociedade mais equilibrada, o qual diminua as diferenças sociais, havendo a justa valorização do trabalho de populações locais. Sendo assim, o Baka Studio, procura estimular a produção local, trabalhando em conjunto com duas famílias indigenas do Xingu, uma da etnia Kalapalo e outra Wuará.

- Design sustentável – reaproveitamento de matéria-prima local: além do reaproveitamento de residuos da industria alimenticia, aqui no brasil, focamos o uso da madeira de demolição e de materiais orgânicos. Utilizamos em nossos projetos madeira e sementes locais encontradas caídas em nosso sitio no interior de São Paulo.

- Educação:

- Do artefato à cultura e ao agente : Temos como proposta principal a divulgação e a valorização da cultura étnica africana, a qual entendemos como uma das principais bases culturais do Brasil. Unindo o trabalho de restauro de peças históricas africanas (encontradas fora de sua comunidade de origem), com a criação de um acervo sobre as mesmas, e a comercialização de réplicas e criações atuais, tem-se como objetivo aproximar a população brasileira com elementos culturais de suma importância.

- Cursos: para a promoção de conhecimento sobre a indenidade Afro-América, o Baka Studio oferece, em parceria com outros instituições, cursos livres sobre a cultura africana e sobre diferentes etnias do continente. Confira os cursos disponíveis on-line e a programação de cursos presenciais.

- Banco de dados: para a promoção de conhecimento sobre a identidade Afro-América Em nosso blog, há um acervo de artigos (acadêmicos ou não) sobre: design, arte, cultura e principalmente sobre cultura africana, máscaras, esculturas étnicas, entre outros.

Camarões:

- Criação e melhoria de infra-estrutura básica nas Vilas Rurais Bamilekes: Já em Camarões, é desenvolvido um trabalho de acompanhamento e suporte de vilas rurais, principalmente da etnia Bamileke, situadas no interior do país. O Baka estimula a produção de artefatos relacionados a cultura étnica tradicional de cada vila, tais como máscaras, escudos e esculturas tradicionais com o objetivo, primeiramente, de divulgar essa cultura local e seus agentes para fora de suas fronteiras; e também com a intenção de comercialização desta produção, pois esta atividade mercantil é única que consolida uma atividade monetária nessas vilas (a entrada de papel moeda), o que é necessário para aquisição de produtos que não são possíveis de se obter através do escambo. Dessa forma, e de mais importância, essa atividade mercantil possibilita a melhoria da infraestrutra local, como a construção de casas de alvenarias, poços e cisternas, entre outros.\

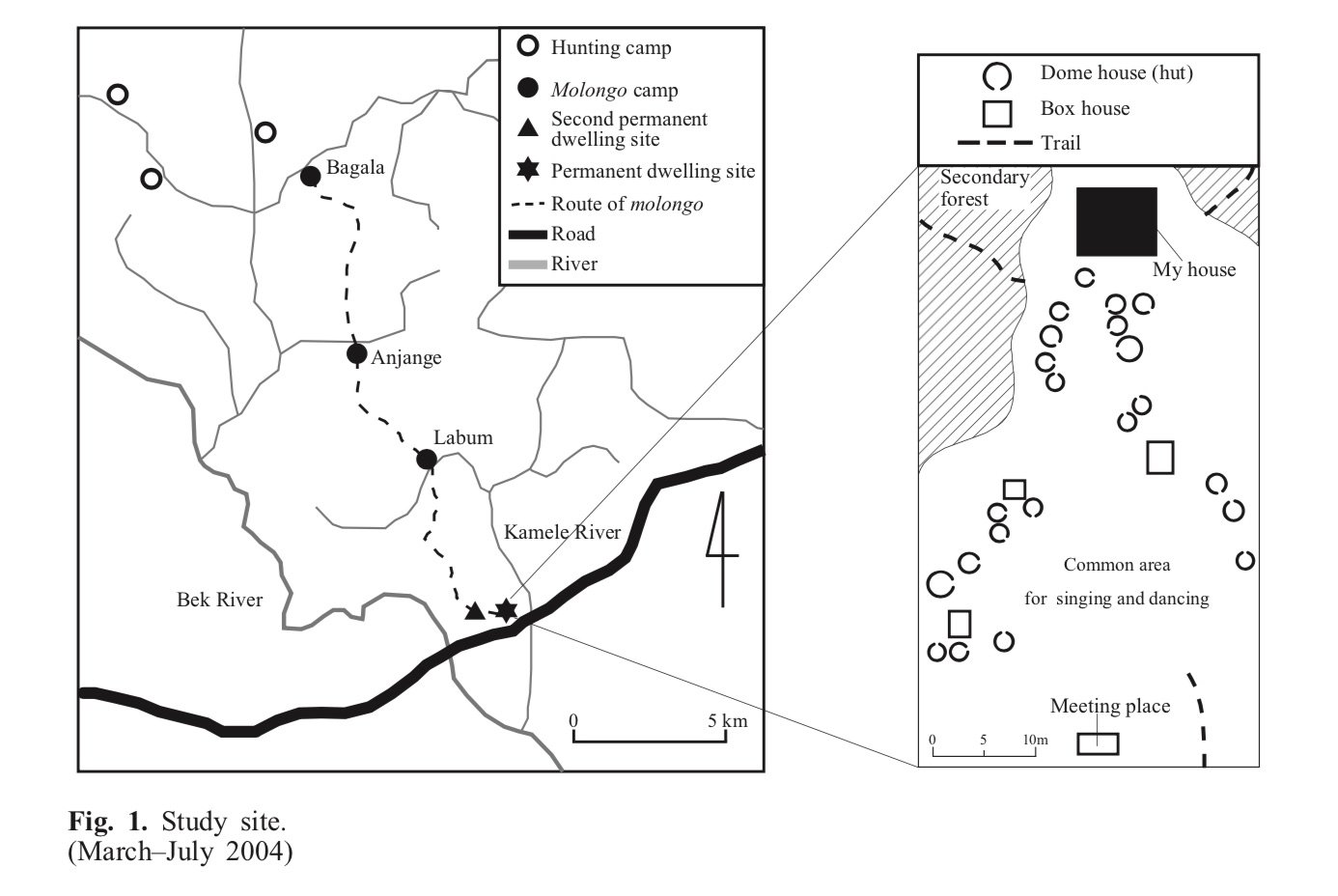

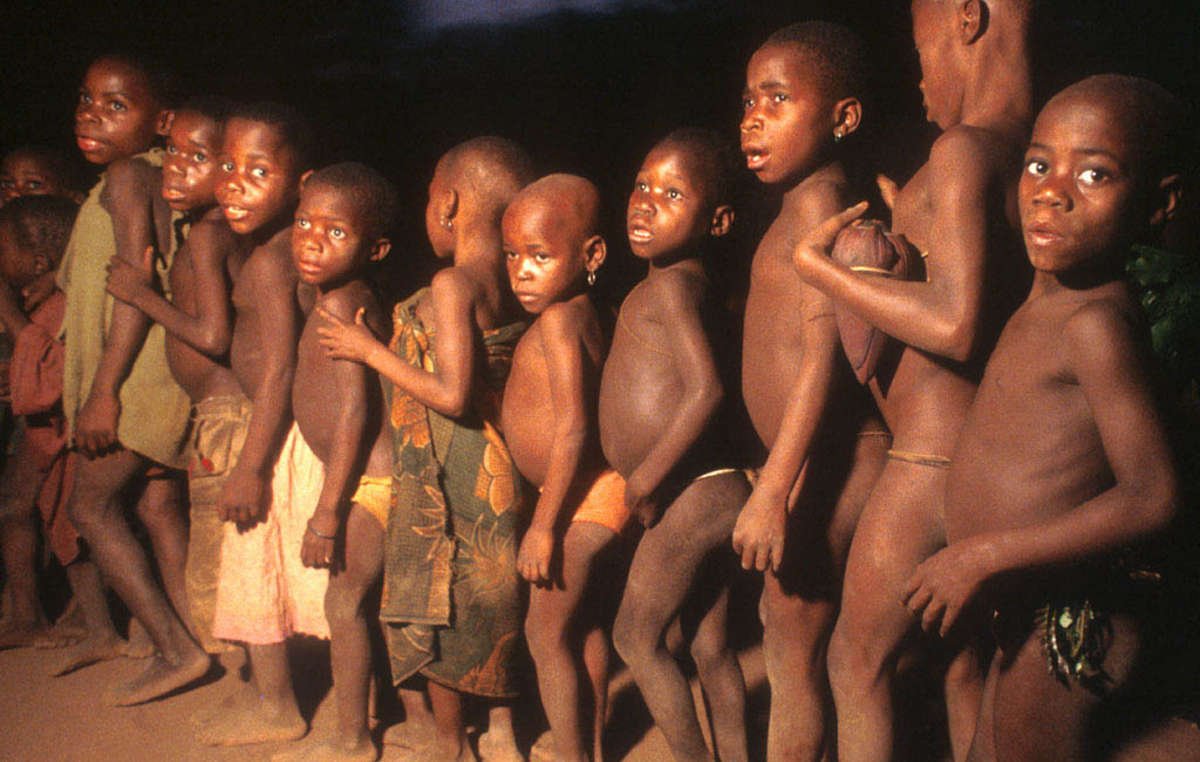

- Etnia Baka: parceria com a ONG Zerca y Lejos

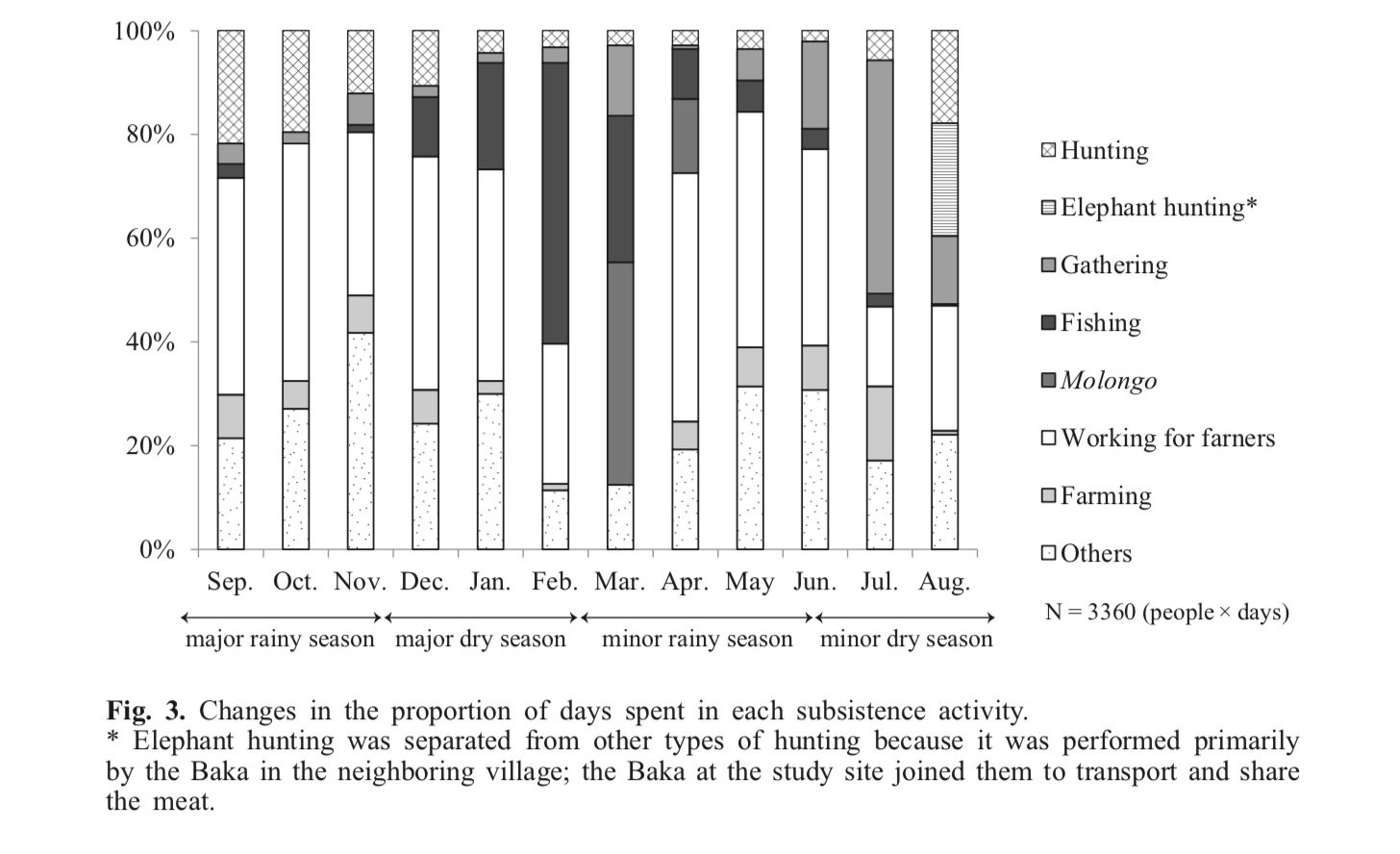

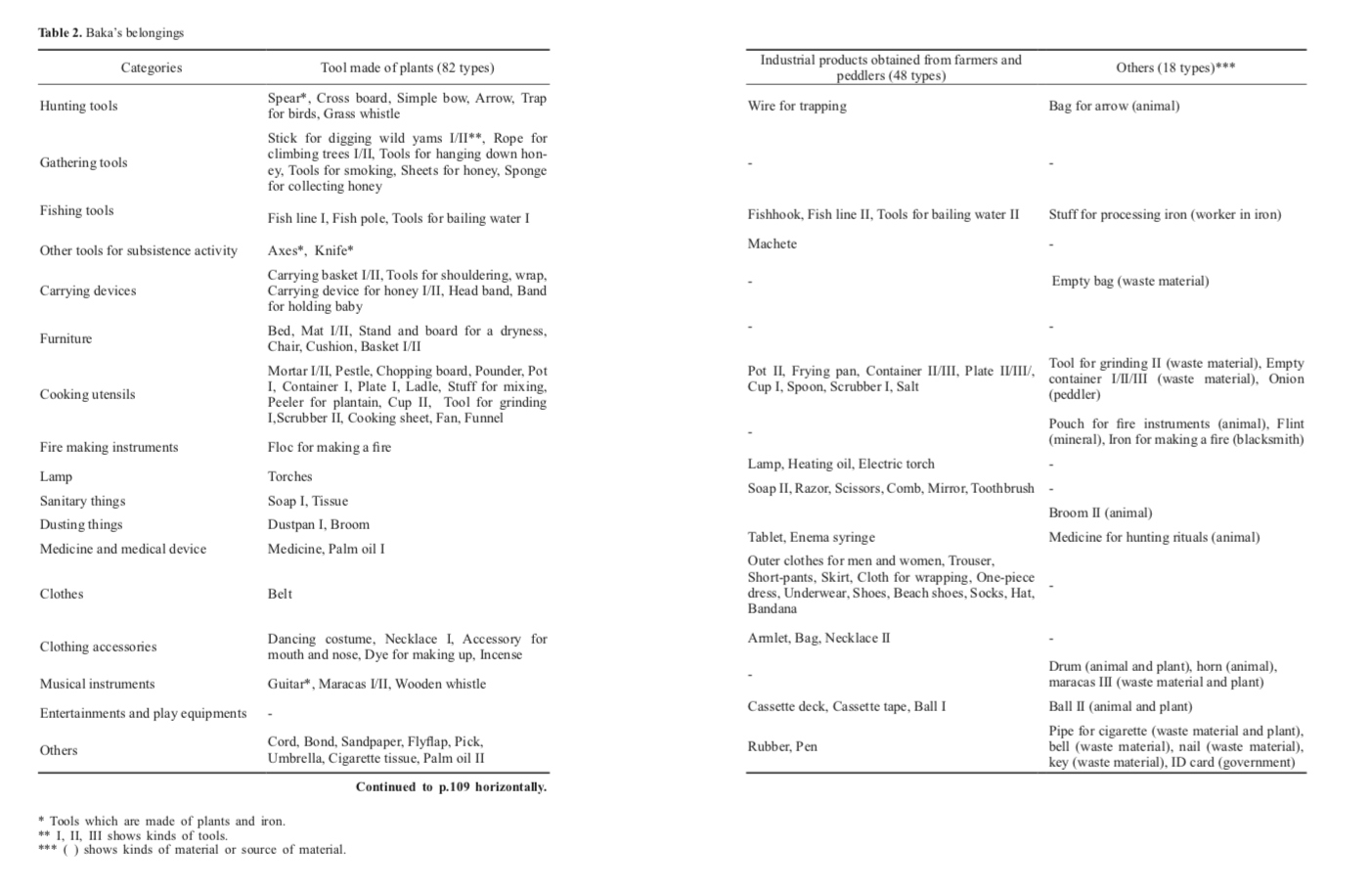

- Direitos humanos: trabalhamos na investigação dos fatores que influenciam o desenvolvimento da etnia Baka e sua atual situação de extrema vulnerabilidade, a fim de disseminar e promover o cumprimento dos Direitos Humanos, com o qual buscamos aliviar a falta de reconhecimento dos direitos da população local no sul de Camarões, especialmente da etnia pigmeu Baka. Para isso, o objetivo é implementar atores no campo que, por meio de um estudo da legislação local, tornem seus direitos mais básicos conhecidos da população em risco. A população Baka, não é reconhecida como cidadãos plenos na sociedade camaronesa . Ao treinar líderes locais, sempre dentro do atual quadro jurídico, o objetivo é criar uma corrente crítica, primeiro dentro dos Baka e depois fazer com que grupos ativistas das etnias bantu entrem em ação. A pressão atualmente exercida sobre as terras da região, promovida pelo setor privado com a colaboração do Estado (grandes projetos agroindustriais, indústria extrativa, desmatamento e projetos) estruturação) e a implementação de políticas conservacionistas (parques naturais, reservas de biodiversidade e santuários), resultam na violação dos direitos humanos das populações locais. Além dessa pressão externa, o grupo étnico Baka está em desvantagem contra a etnia majoritária, os Bantus. Isso se traduz no difícil acesso dos Baka à sociedade, uma vez que carecem dos direitos fundamentais mais básicos, como acesso à justiça, marginalização no acesso à educação ou pouca participação política. Com este projeto, trabalhamos com comunidades e associações locais para promover a observância dos direitos humanos nas populações mais marginalizadas de Camarões.

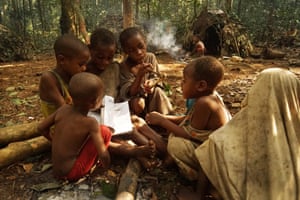

- Educação: acreditamos que a educação é a ferramenta mais eficaz para alcançar a integração igual entre meninos e meninas pigmeus com os de outros grupos étnicos. Por esse motivo, consideramos que a sala de aula é o espaço perfeito para trabalharmos juntos desde a infância e a educação em valores de igualdade, que são o nosso compromisso de alcançar uma sociedade mais justa. A abordagem é desenvolver um projeto educacional sustentável a longo prazo e capaz para cobrir tantos quilômetros, cidades e crianças quanto possível. O principal objetivo é garantir o acesso à educação para todos os menores da etnia pigmeu Baka e facilitar o acesso ao ensino superior, em igualdade de condições com o restante das crianças no sul dos Camarões. agora eles são os que defenderão sua dignidade como indivíduos e como comunidade amanhã. Queremos dar a esses jovens a oportunidade de escolher um futuro digno, sem perder seus costumes e tradições, reforçados e apoiados pelos Centros Comunitários de Educação Infantil e por professores do mesmo grupo étnico. O Baka Studio faz doações mensais para a omg Zerca e Lejos para auxiliar no fornecimento de material escolar por um ano para todos os meninos e meninas do projeto de assistência social a menores em risco. É realizado na área do Grande Djoum antes da detecção de vários casos de crianças em situações de risco e negligência significativos. O horizonte mais promissor com o qual podemos sonhar é que os meninos e meninas pigmeus Baka de hoje podem se tornar os atores de seus desenvolvimento próprio e é por isso que trabalhamos incansavelmente. Além disso, seguindo nosso compromisso com a solidariedade, a compreensão dos outros e a justiça social, em Madri há um forte compromisso com o voluntariado e a educação para o desenvolvimento nos centros educacionais.

COMO COLABORAR:

- Compre nossos produtos, pois a renda é revertida para manutenção de nossos projetos

- Faça uma doação:

- 20 reais = material escolar suficientes para um mês para as crianças do projeto educacional da etnia Baka desenvolvido em parceria da omg Zerca y Lerjo

- Seja um voluntário em uma instituição parceira na África: