Um Ensaio Fotográfico sobre os Bakas

Susan Schulman’s photo essay reveals life in the Dzanga-Sangha forest, where Baka Pygmies are struggling to maintain their traditional way of life in the face of logging, poaching and a lack of healthcare.

As the Baka Pygmies of the Dzanga-Sangha region of Central African Republic struggle to live in their traditional ways, they find themselves caught between worlds.

Baka split their time between village and forest. Here, in their forest home, life continues in the face of many challenges, ranging from poachers to ill health. Destructive developments within the forest, such as illegal logging, also pose a threat.

Historically, the Baka have been kept as slaves by the Bantu, an ethnic group from the neighbouring Democratic Republic of the Congo. The Bantu are known locally as ‘Bilo’. Persecution by the Bilo is inescapable.

Malala and her 20-something daughter Agate tell of their experience of being slaves in DRC.

‘When you’re owned, you’re obliged to work in the plantations. They will give you alcohol and smoke and, sometimes, manioc leaves for lunch but they won’t pay,’ Malala explains.

Baka would alternate time on the plantation with time in the forest. Owners would give them shotguns with a certain number of shells to bring back meat for them.

‘If he gives you four shells and you only come back with three animals, they beat you really, really badly,’ says Malala. ‘There is terrible trouble. Some will even kill for not bringing back the shell.’

Agate rebelled. ‘When I was a child, Mother told me that that man was “our Bilo” and that we were owned. But when I grew up, I refused. I said I am not that kind of Baka. I would make my own decisions.’ It was not that easy. Agate’s father’s owner claimed her. When she refused, he followed her to CAR and demanded payment from her husband.

When not in the forest, these Baka Pygmies live in Yandoumbe village. While outright ownership is disappearing, Bilo attitudes of superiority and entitlement towards the Baka persist. Below, a Bilo man accuses a Baka boy, right, in a dispute over the price of a beignet pastry.

In the forest, the despondency of the village is left behind and traditional life resumes.

Both women and men hunt every day. Baka are obliged by laws – originally designed to protect the forest – to hunt using only their traditional nets and spears.

The staple food of the Baka is the blue duiker, a forest antelope. Here, they enact their traditional hunting ceremony.

Their way of life is under constant threat from poachers, who have no inhibitions about using guns. ‘The reserve is supposed to be for the Baka, but it is a joke,’ says Louis Sarno, originally from New Jersey, who has lived with the Baka for 30 years. ‘It is filled with guns and snares. Hunting with guns and snares is the biggest threat to the Baka way of life. They now go into the forest and often [come back] hungry.’

Below, Agate prepares some of the spoils of hunting – a tortoise and a duiker.

A hunter sharpens his spear tip wearing a mock Apple watch.

Poachers hunt at night, using flashlights to stun the duikers and shoot them as they stand paralysed in the light. These poachers – all Bilo – killed seven duikers and one monkey in their night of hunting.

The poachers cook up the monkey’s head (pictured below right) at the Baka camp.

Guns and poaching are greatly accelerating the depletion of the forest. Everyone recognises these poachers as having been part of the (largely Christian) anti-balaka militia. Local NGOs have been unable to protect the forest from poaching.

‘If things continue as they are now,’ says Sarno, ‘Baka won’t be going into the forest. They will become like serfs to the Bilo again. They will lose their humanity.’

Poaching is not the Baka’s only problem.

Central African Republic (CAR) ranks 187 out of 188 in the 2015 human development index. The average life expectancy is 49 years of age. Unicef says that CAR has the eighth highest under-five mortality in the world. Figures are even worse among the Baka.

Tuberculosis is approaching crisis level; hepatitis B and malaria are endemic. Almost all of the children test positive for malaria.

Sarno estimates that half of Baka children don’t make it to the age of five. It doesn’t help that there is no doctor at the local health clinic. Advertisement

The nearest professional medical attention is at Nola, 120km away, so Sarno, who has no medical training but felt compelled to help, has taken on the role. Supplied with medicines by the German NGO Action Medeor, he does his best to diagnose illnesses and dispenses drugs.

It is not a job Sarno wants to be doing. ‘The burden of being diagnostician and doctor keeps me up at night. And, if someone dies, you can be blamed too.’

Jiggers are a scourge of the Baka. This parasite lives in soil and sand, and burrows into feet; if it is not extracted it causes infection and eventually deformity. In the image below, they have infested the boy’s left foot. His is a mild case compared with those of the many children crippled by infestations.

Traditional medicine remains the first port of call for many Baka, and an overwhelming belief in sorcery and witchcraft often creates a fatalist attitude that stops them seeking proper medical treatment and sticking to drug regimes. The woman pictured below is being treated for a toothache, her cheek stained where traditional medicine has been applied.

Badangba, who doesn’t know how old she is, has seen sickness claim many lives. ‘Lots of illnesses grab the children here; a lot of children die,’ she says. ‘There is a lot of sadness for mothers, as their arms are empty and they don’t know what to do.’

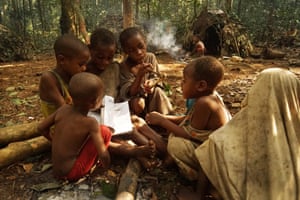

The future looks certain through the eyes of Baka children. Here, they gleefully mimic the traditions of their community.

They enact the daily hunting ceremony, summoning up the leaf-cloaked forest spirit, Bobe’e.

But for the community’s young people, the future seems far less clear.

For these young people, there are few opportunities. Hunting used to be easy: the forest used to be teeming with wildlife. But the severe depletion of animals has changed that. Hunting – and consequently eating – is now less reliable, tarnishing the appeal of traditional life for youth.

Yet village life also holds little promise. The schoolteacher shows up only sporadically, drunk and mean, and the only occasional work is available from the Bilo, who offer the paltry sum of $1 for five days’ hunting in the bush but who often fail even to pay the fee promised. Young people are floundering, confused and too often taking refuge in tramadol, a powerful synthetic opiate available in nearby Bayanga town, and in glue-sniffing.

Parents are concerned.

‘It is really bad for them to be sniffing glue and taking drugs,’ says one. ‘If they keep on doing that, they become lazy and then they won’t go into the forest any more.’

This would spell the end of traditional Baka life.

This article was amended on 5 May 2016 in The Guardion.com